It’s not common to be called a veteran at age 23, much less a living legend. But Stevie Wonder was always a clear exception. After all, he practically dominated the Motown era in his teens. He had also already surpassed the 10-album mark seven years into his career. Obviously, they were dealing with a prodigy, and he was in it for the long haul. Enter the 1970s, or, in his case, his adulthood, and the masterpieces just kept coming.

With staples such as “Superstition” and “You Are the Sunshine of my Life”, 1972’s Talking Book felt like a tough act to follow. But, as it turned out, he had just entered his Classic Period and had yet to outdo himself.

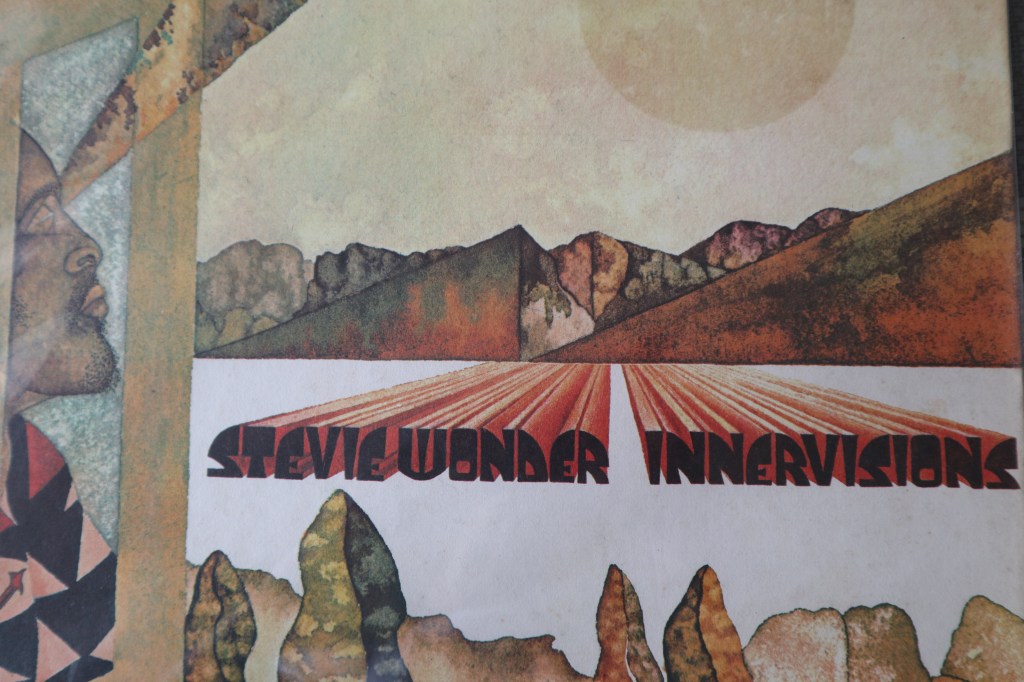

Then came Innervisions, which was bound to be legendary for different reasons. Unlike the 15 albums that preceded it, it was his first solid shot at a statement.

Much like his entire discography, this was substantially his own work – from writing and composition to production. He also played most instruments and particularly made prominent use of synthesizers here.

While the nine tracks seem thematically diverse, they’re all bound by one premise: the black man’s urban struggles during that era. Come to think of it, some of those struggles even linger to this day. With its stark and well-observed imagery, it might as well be a soundtrack to a movie musical. Such vision for someone born blind, so they said.

The album has its share of soulful ballads, such as the sublime “All In Love is Fair” and “Golden Lady”, which captured admiration to the point of near-worship. It’s the remainder that constitutes his most harrowing work. Even the dance floor ditty “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing” is about a man protecting his woman from harsh realities.

The opener “Too High” sets the hard-hitting tone. Despite its simplicity, it’s a straightforward depiction of drug abuse. The more it escalates in tempo, the lower its protagonist spirals. It’s bleak and it doesn’t end well. It’s followed by “Visions”, which ruminates on dwindling peace.

The third cut, “Living for the City”, completes that trifecta of gritty openings. It’s the most resonant piece in the album, replete with monologue of a man arrested and incarcerated without due process. It was the most straightforward attack on racism at the time. Sound effects like sirens and prison bars added frightening touches.

While the third track proved to be the most chilling, the final track proved most courageous. With lines such as “Makes a deal with a smile/Knowing all the time that his lie’s a mile”, “He’s Misstra Know-It-All” was said to take a jab at politicians, particularly then-president Richard Nixon.

Two spiritually themed tracks complete this line-up. There’s “Jesus Children of America”, which pays homage to his Christian roots. Then, there’s Side B opener “Higher Ground”, which intriguingly touches on Buddhist principles. It’s as powerful as a carrier single could get, with references to Karma, reincarnation, and fulfilling one’s life purpose. It’s also eerily prophetic. When Wonder survived a near-fatal car accident not long after the album’s release, the parallels couldn’t be more resonant – especially the line “I’m so glad that he let me try again”.

And reach higher ground, he did. He didn’t only make a full recovery, but he also successfully redefined himself that decade. In doing so, he affirmed his timelessness and would sustain his evolution in years to come.

Innervisions went on to win the Grammy for Album of the Year. In fact, it was the of his three consecutive wins in that category, the succeeding two being 1974’s Fullfillingness’ First Finale and 1976’s Songs in the Key of Life. But apart from starting that streak, the album remains his most provocative and most hard-hitting piece of work yet. 50 years later, the messages still resonate loud and clear.